THE BEST MINDS OF MY GENERATION (2016) - Research Paper and Illustration Series

Note: This is an excerpt. The full essay is available by request through the contact form.

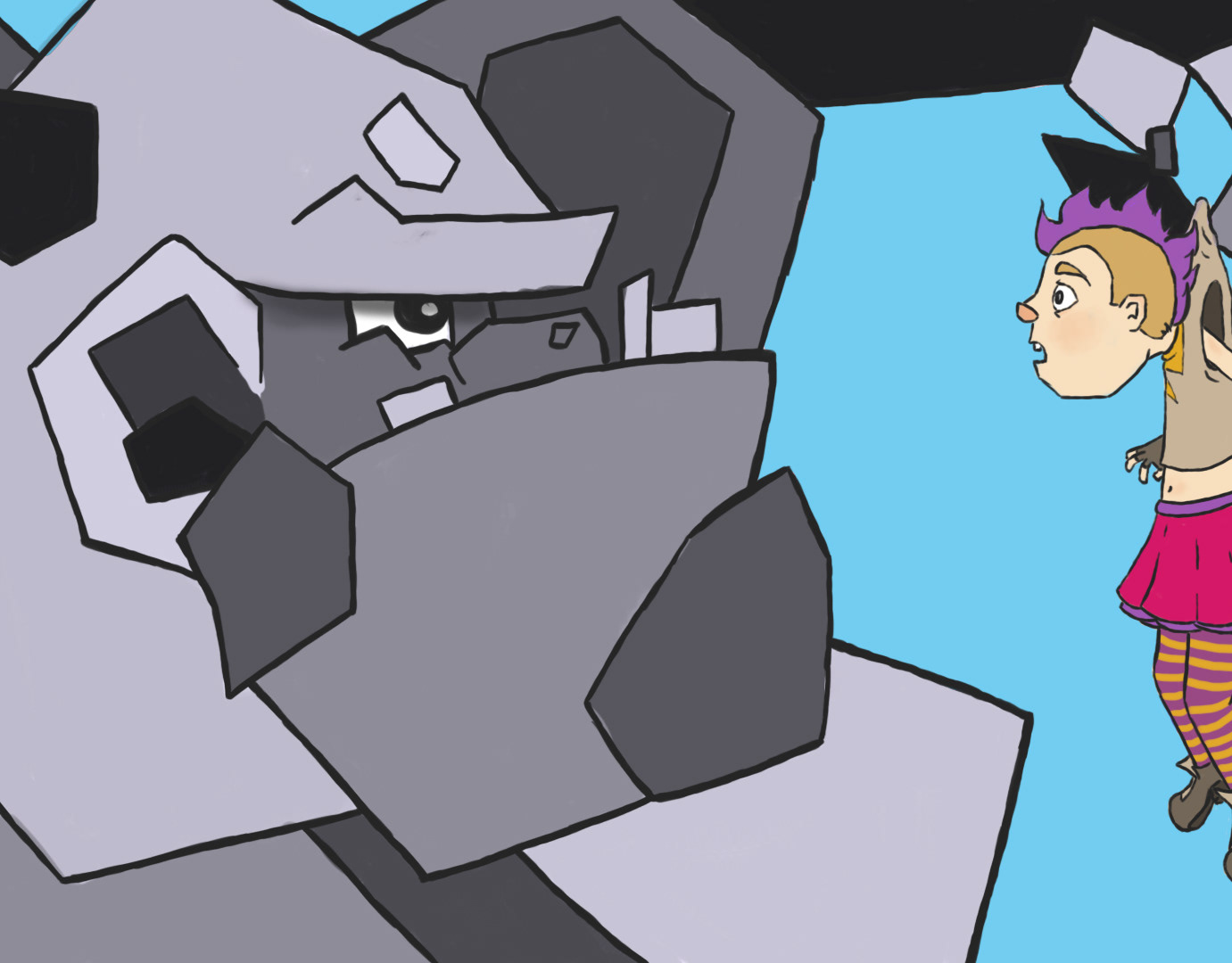

This research paper was written for an early undergraduate research class focused on subcultures. In addition to researching and writing the paper, I created a series of illustrations tracking the Beats and their influence throughout culture after the height of their literary movement. As part of my presentation for the class, I completed a video project showing the process of creating the paintings and displaying them together. This research built off work from an independent study I completed as a high school senior.

The text of the paper can be found on the left hand side. The right hand side contains the final illustrations. Click on the images to see larger versions. A video compilation showing the process of creating the illustrations accompanied by a recording of Allan Ginsberg reading his famous poem, "Howl," can be found at the bottom of the page.

The text of the paper can be found on the left hand side. The right hand side contains the final illustrations. Click on the images to see larger versions. A video compilation showing the process of creating the illustrations accompanied by a recording of Allan Ginsberg reading his famous poem, "Howl," can be found at the bottom of the page.

"The Best Minds of My Generation": Sexuality, Censorship, and the Cold War in Beat Generation Culture and Literature

War profoundly affects the mentality of a society and its people. As a result of war, the world is left deeply shaken and traumatized by the changes it inflicts upon people’s lives and worldview. The response to this trauma is the true test for a society. The question is not just if the society will be able to come back stronger physically and economically, but morally and spiritually as well. The truth remains that societies often disregard the individual mental and emotional well-being of their citizens in favor of capitalizing on the gains of war and controlling the population in order to keep an economic and political advantage. As a response to the lack of concern for humanity from higher powers, philosophical and art movements step in to fill the void. Despite the backlash that often comes from the dominant society, these movements work to remind citizens of the important parts of life beyond material items. Members of the Beat Movement created art and engaged in lifestyles that rejected 1950s conformist, consumerist culture. Founded in the mid-1940s in New York City by several former Columbia University students, the movement soon grew to encompass a small groups of mutual friends spread throughout the United States, and ultimately went on to influence large swaths of American culture. Fear of communism and nuclear attack gripped America in the early years of the Cold War after WWII, but this fear was disguised by pastel advertisements for new household appliances, suburban homes, and hotrod cars pushed by American corporations and media. The Beats exposed a darker side of America—downtrodden, outcast, and looking for something greater than the supposed ideal of standard American living. They saw the horrors that mainstream America was able to inflict upon those who did not fit in to the image that was already made for them. Influenced by Transcendentalism and Eastern religions, the Beats wanted to create and live spontaneously and authentically to gain a “new vision” of the world that was fulfilling to them as individuals. The country generally despised the Beats’ contentious lifestyle, from their substance abuse and unabashed sexuality, to their obscene language and perceived petty criminality. The Beat Generation revolutionized American culture by rejecting consumerism and the elitism of academia through the creation of provocative, alarming art and a subversive way of life that exposed the irrational, repressed fears of the dominant culture and the need to dismantle unthinking conformity under capitalism in order to gain a greater sense of truth and fulfillment.

Allen Ginsberg, 1979, based on photo by Michiel Hendryckx.

The Beat Generation engaged in lifestyles focused on individual fulfillment fueled by intellectual and spiritual experiences rather than higher economic status, which was the arbitrary image of the ideal standard of living in 1950s America. This was a rejection not only of consumerism, but of the fear that drove consumerism as well. The years immediately following WWII were the beginning of the Cold War, a time of tension and uneasiness for many Americans. Despite this, the media and corporate America capitalized on the booming success of the postwar economy powered by government programs such as the Marshall Program and new, cheap household technologies such as color television, Tupperware, and microwaves (Sterritt 26). However, this seemingly positive boom of consumer America was laden with the dark, political undertones of the Cold War. Despite economic prosperity in the U.S., the psychological and spiritual well-being of the nation was neglected as everything associated with the Cold War—fear of communism, McCarthyism, Soviet attacks by nuclear invasion or infiltration—loomed over citizen’s minds. (Sterritt 26). Additionally, troubles at home caused disruption in daily life through a widening gap between the rich and poor, oppression of African Americans, homophobia, and sexual repression present throughout society (Sterritt 26). These fears, in particular fear of foreign threats, fueled the “containment culture” of the Cold War. This culture manipulated the insecurities of Americans, turning them into consumers who felt compelled to acquire the products advertised to them, lest they be seen as differing from the norm (Johnston 105). Corporations created a need among consumers that had not previously been present, turning consumers to excessiveness instead of the thriftiness that America had previously been known for (and was imperative to the war effort in the 1940s). Beat writer William Burroughs wrote about the concept of a “created need” in Naked Lunch, describing, “A world of manipulated needs that serve mainly to keep those who satisfy them in power… its members are driven by their need to control and dominate” (Johnston 108). In Naked Lunch, Burroughs is referring to a dependency on drugs, or “junk”, that the government in the book created for its citizens to keep them always dependent on the higher powers. The drug epidemic in the book is a clear analogy for capitalism. Many of the Beats railed against capitalism for the degrading dependency it created for all citizens. Capitalism is a system that does not allow citizens to be fully independent. To survive, citizens in a capitalist society will always have to play by the capitalist rules and they will always lose the game because it is rigged in favor of those who already possess privilege, wealth, and power. After WWII, the American government and corporations thrived on capitalism and the need they created for citizens because they were more readily able to convince people that they had to buy certain items to achieve a certain standard of living that had been sold to the American public as “perfect”. To live with anything less than the ideal standard was to be imperfect in the eyes of society, and this sentiment still runs strong in America today.

Jack Kerouac, 1956, based on photo by Tom Palumbo.

Conformity was also imperative to the culture of 1950s America. This seems ironic, given that Nazi Germany and the communist Soviet Union, some of the institutions most feared and despised by many Americans at the time, thrived on conformity and lack of individual thought. But conformity was a requirement of the time due to the aforementioned fear of communism. Anybody not adhering to the “American standard” could and would be deemed a communist or an outsider of an undesirable sort. This was the dark mindset brought onto the American public through its own corporate, political, and media powers. These powers worked together through the “created need” to form “happy” consumerist conformity and what would become known as the norm of the 1950s, with a concentration on the stereotypes of the white, nuclear family and gender roles (Johnston 106). The preoccupation with conformity has been seen by some as an indication of “soft” totalitarianism in America, as this attitude has lent itself to promoting political propaganda (Johnston 107). In an attempt to discourage unsavory political activity which could endanger the country, America instead created a system that actually mimicked its enemies in terms of conformity and blind acceptance of figures of authority. This system swallows or repulses all alternative mindsets.

This was the system the Beats rejected with their lifestyle. It was not only the surface-level standard of the suburban homes and clear family unit funded by a man’s stable 9-to-5 office job that they rejected—the Beats rejected the entire system that culminated to create this image and present it as the norm and ultimate goal of life. They found the system and the needs created by it to be frustrating, degrading, and oppressive; the Beats made full public criticism of American consumer culture that had never been seen before (Johnston 104). The truth of the matter is that the Beats were not actually fighting the system; more often, they chose to simply opt out of it (van Elteren 78). They achieved this non-participation in the system through their creative and spiritual outlets as they searched for a “new vision” (Sterritt 27).

The Beats made their own way of living outside of the system, characterized by action. The action was a fast, fervent spasm of energy in an attempt to live in that active state (van Elteren 73). Much of the Beats’ art and literature is characterized by this fast pace of living and presenting information. They were “mad to live,” and behavior that reflected this was essential (van Elteren 75). Continuous, intense conversation was a social ritual in Beat life, and this has been immortalized in several Beat works (Johnston 104). One of the lines from Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” shows people who “talked continuously seventy hours from park to pad to bar to Bellevue to museum to the Brooklyn Bridge…” (Ginsberg 11). This shows the passion for full, spontaneous lives that drove the Beats to live in such an eccentric manner. Especially at the beginning of their careers, they had to keep moving, generating ideas, and throwing things out into the world to see what would happen. They were testing the reaches of the human experience (van Elteren 81).

The Beats were in a continual search for a “new vision” or “IT,” as the concept is referred to in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. This “new vision” was a point of ecstasy that could not be experienced within the confines of mundane, everyday life (Johnston 104). They tried to find this point through many different means, such as simplicity and freedom from possessions, spiritual independence, and sensory enhancers such as hallucinogenic drugs (van Elteren 76). In their writing, Beat authors attempt to communicate the “new vision” to the audience. Reading Beat literature is like being thrust into the experience of the Beats, drug-induced hallucinogenic images and all. The Beats wanted a fuller and more personally satisfying experience of human life, and attempted to attain it through sometimes extreme means.

Some would see it as a downside that these extreme practices in search of a “new vision” often lead to poverty for the Beats, but the group saw it as an intellectual gain to cast off the unnecessary evils of the consumer world (van Elteren 79). The Beats’ way of life led them into voluntary poverty as they tried to escape the corruption of the commercial world. As the U.S. entered into a time of “New Prosperity,” the Beats came into a lifestyle of “New Poverty” which directly opposed it (van Elteren 75). The Beats highly regarded the living conditions of a group of Americans they called the “fellaheen,” an underclass of manual workers, drifters, hobos, sex workers, and the like who were upheld by the Beats as “primitive” and “in tune with the cosmos” (Sterritt 28). They offered an alternative to the dominant society and they existed outside the dream of wealth in America (Johnston 119). This is exactly the lifestyle the Beats were looking for. They searched for a way to escape the system that worked to distract and remove them from their quest for the “new vision” and they had found it in the fellaheen. Though some of the Beats did partake in this lifestyle for short periods of time near the beginning of their career, they entered into it with the freedom and security to leave at any time, unlike those forced into these roles for survival. The Beats’ work showcases many of these forays into the underbelly of American life. For instance, On the Road shows Sal Paradise (an alter-ego of author Jack Kerouac) hitchhiking across the country several times throughout the course of the novel with migrant workers and a few times Sal himself ends up working for a short period in the fields. On one of his first rides out West, Sal describes his life with, “… a truck… with about six or seven boys sprawled out on it, and the drivers, two young blond farmers from Minnesota, were picking up every single soul they found on that road—the most smiling, cheerful couple of handsome bumpkins you could ever wish to see, both… earnest, with broad howareyou smiles for anybody and anything that came across their path” (Kerouac 24). These people had the spirit that the Beats were searching for. The fellaheen, as romantically immortalized by the Beats, were simple and full of life, and the Beats tried to experience life in the same way.

William S. Burroughs, 1977, based on photo by Marcelo Noah.

Books that have been historically challenged, banned, and censored. Featured in the center are "Howl" and Naked Lunch, Beat literature famously targeted in two censorship trials.

Many Beats openly expressed same-gender attraction and lived in same-gender relationships (Allen Ginsberg is the most famous of these) which played a role in paving the way for modern queer liberation movements.

A personal piece. Beat literature continues to be taught in classrooms today.

Works Cited

Bisbort, Alan. Beatniks: A Guide To An American Subculture. n.p.: Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press/ABC-CLIO, c2010., 2010. COLUMBIA COLLEGE’s Catalog. Web. 12 Oct. 2016.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Howl.” Howl and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Bookstore, 1956. Print.

Holladay, Hilary, and Robert Holton. What’s Your Road, Man? : Critical Essays on Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. n.p.: Carbondale : Southern Illinois University Press, c2009., 2009. COLUMBIA COLLEGE’s Catalog. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

Johnston, Allan. “Consumption, Addiction, Vision, Energy: Political Economies and Utopian Visions In The Writings Of The Beat Generation.” College Literature 32.2 (2005): 103-126. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 12 Oct. 2016.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. 1955. New York: Penguin Books, 1991. Print.

Marler, Regina. Queer Beats : How The Beats Turned America On To Sex. n.p.: San Francisco : Cleis Press, c2004., 2004. COLUMBIA COLLEGE’s Catalog. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

Sterritt, David. “Beats, Beatniks, and Beat Movies.” Cineaste 39.1 (2013): 26-29. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

van Elteren, Mel. “The Subculture Of The Beats: A Sociological Revisit.” Journal of American Culture (01911813) 22.3 (1999): 71-96. Humanities International Complete. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

Bisbort, Alan. Beatniks: A Guide To An American Subculture. n.p.: Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press/ABC-CLIO, c2010., 2010. COLUMBIA COLLEGE’s Catalog. Web. 12 Oct. 2016.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Howl.” Howl and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Bookstore, 1956. Print.

Holladay, Hilary, and Robert Holton. What’s Your Road, Man? : Critical Essays on Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. n.p.: Carbondale : Southern Illinois University Press, c2009., 2009. COLUMBIA COLLEGE’s Catalog. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

Johnston, Allan. “Consumption, Addiction, Vision, Energy: Political Economies and Utopian Visions In The Writings Of The Beat Generation.” College Literature 32.2 (2005): 103-126. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 12 Oct. 2016.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. 1955. New York: Penguin Books, 1991. Print.

Marler, Regina. Queer Beats : How The Beats Turned America On To Sex. n.p.: San Francisco : Cleis Press, c2004., 2004. COLUMBIA COLLEGE’s Catalog. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

Sterritt, David. “Beats, Beatniks, and Beat Movies.” Cineaste 39.1 (2013): 26-29. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.

van Elteren, Mel. “The Subculture Of The Beats: A Sociological Revisit.” Journal of American Culture (01911813) 22.3 (1999): 71-96. Humanities International Complete. Web. 13 Oct. 2016.